craftsmanship

Hi from France! More about that later. As I traveled here over the weekend, I stopped for a night in Brussels to visit a friend, hear an opera (Fauré’s Pénélope–hear this score if you can, OMG), and see an exhibition of Japanese prints.

The exhibition was a last-minute decision. I had a morning free before re-starting my travel, and I thought I’d see how I felt–maybe I’d prefer to while away a couple hours over a coffee or two, read and people-watch. But I woke up with lots of energy and decided to go. And now I can’t imagine having not seen it. It was so enthralling that I nearly missed my bus because I lingered too long.

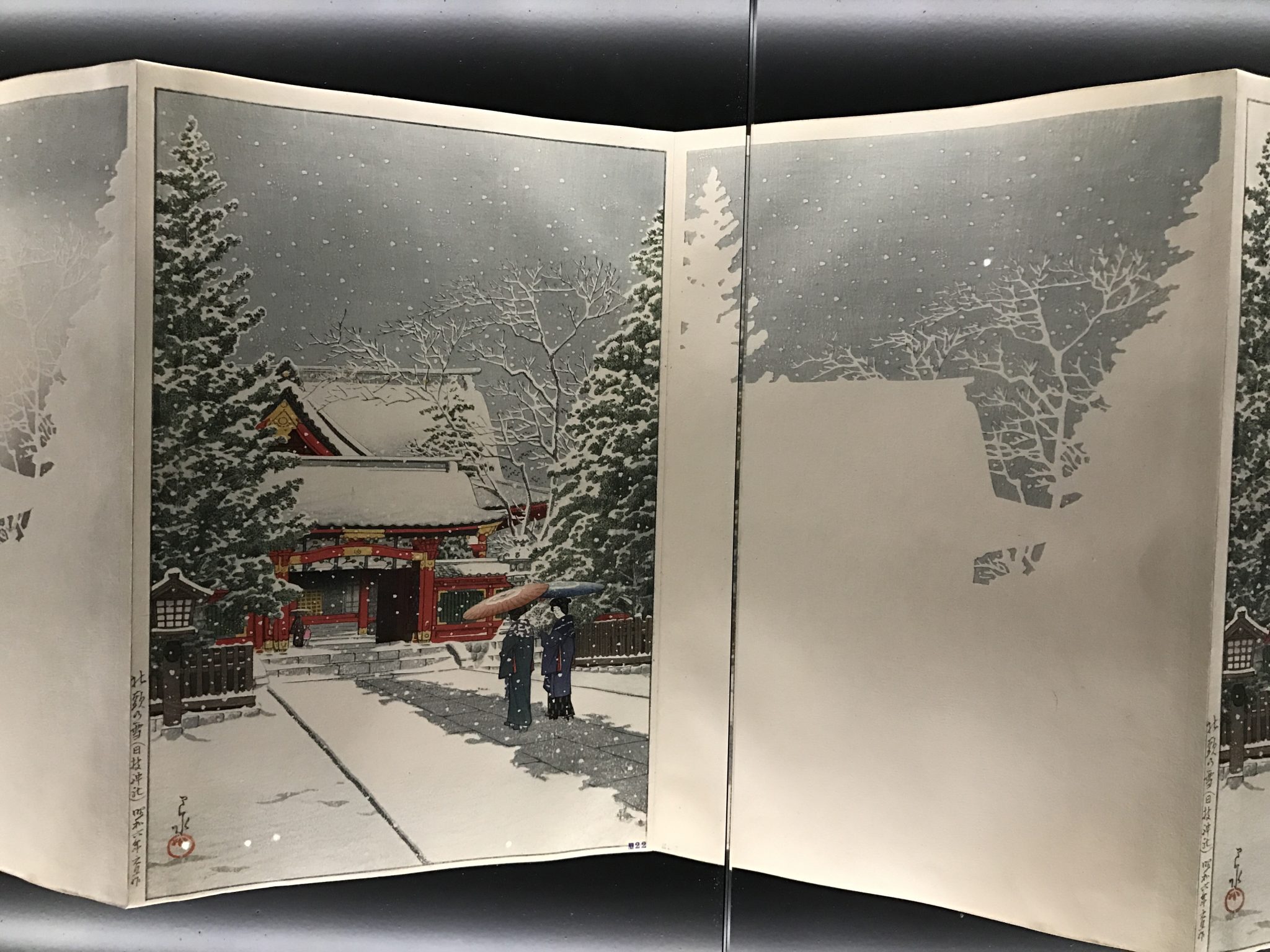

The exhibition spanned several centuries of fine-art printing, and each room was extraordinary in its own way. But the image above was one of the first things I saw, and it set the tone. It’s part of a long horizontal case–thirty feet long, maybe–displaying what looks like an accordion-folded book (the 19th-century artist is Kawase Hasui). Starting at the rightmost end of the case, you see at first a single-color engraving–the outlines of a scene pressed in a grayish ink. As you continue to move down the book, each fold showed an additional single-color print that was to be layered in, and on the left the cumulative effect each new print was having on the whole picture. So, after the grayish outline, some tiny blobs of brown were added, and later the yellow and then the red of the temple popped vibrantly. One entire print layer might be the tiniest pinprick of purple to darken the pattern on a kimono; another was a light wash of green to give the trees their first color, followed by a darker shade of green, distributed more irregularly, to create shadows. Many layers added just the subtlest dusting of gray to nuance the texture of snow or sky.

And each of these additions was a separate print–a separate carving of a wooden block, application of color, and rubbed overlay on what had come before. Each one had to be flawlessly calculated to line up with the rest, including the tiniest possible little daubs. Seeing each layer printed separately from the picture, sometimes just two strokes of dark red for kimono sashes, sometimes entire trees, and sometimes little gray shapes to mark divots in the snow, I found myself gasping audibly at the exactitude, realizing that a part of the picture that hadn’t yet made sense had actually been planned minutely. My moment of greatest awe came when I saw the image above: despite the detail already given to the women’s clothes and the exterior of the temple, some of the tree branches above had remained just single lines, but in this pressing, the grayish sky print left bare enough white around these lines to perfectly indicate the snow accumulating on the trees. The negative space had been as finely mapped as the color.

An exhibit that showed one arduous and detailed piece of work–the cumulative printing of a colored picture, of perhaps twenty separate colored pressings–hinted at an even more extraordinary piece of work–the artistic process of the person who first conceived the image and then had to map, so finely and ingeniously that I could scarcely believe it, how the picture would slowly come into being. This person had to be able to envision it all before actually seeing the layers come together–it had to be planned in the mind without a visual reference from the very first outline. And even more amazing that they found a way to show us the thought process, too–it’s from the late 19th century, when process was being explored and blown apart and re-made.

By putting this particular display in the first room, the exhibition made sure that I knew how much extraordinary work, vision, and craftsmanship went into every single picture I’d see thereafter.

It reminded me also that many artistic processes are related. The point of a finished product, in many cases, is to hide your seams–to give a beautiful shape but to disguise the work it took to get there, to make it feel spontaneously formed, perfectly sprung in one. It’s the same with preparing music… we work and work and work, incorporating technical mastery in slow and small pieces, going back and layering on another level of understanding, breaking it back down, studying each word and gesture and musical marking, allowing our evolving understanding of each element slowly to bring the whole further along–with the goal of eventually making it sound as though we’d just fallen out of bed that day and given perfect musical utterance to a complex thought. Of course, seeing or hearing such a result is wonderful and often moving. But I’m so glad when someone allows us into the process, as this book did. It gives you all the more appreciation for the end result.

(At least that’s what I’m telling myself vis-a-vis my neighbors in my Airbnb, who are getting really intimate with my preparation of virtuosic Mozart.)

No Comments